The North Carolina race for Senate in 2016 was one of the most competitive – and expensive – races in the country that year. The election pitted Republican incumbent Richard Burr against the lesser-known Democrat Deborah Ross, a former state House Representative, in what turned out to be a closer race than anyone expected.

Burr held a narrow lead through much of the campaign, but that lead began to shrink beginning in October. The candidates were tied in polls conducted in the final weeks of the campaign. But in the end, the incumbent Republican Burr captured 51.12% of the state’s votes, compared to Democratic opponent Deborah Ross’ 45.32% (Sean Haugh, libertarian candidate and pizza delivery driver got 3.56% of the vote).

While the two campaigns may have been drastically different in terms of their political platforms and public image, what they did have in common was their willingness to tap into the power of data, technology and social media. Both employed a digital campaign strategy. Both teams made digital content and strategic, data-informed messaging priorities.

And in doing so, both teams found success.

While much has been written about Barack Obama’s masterful use of technology, and more recently about the social media success of Donald Trump, little has been written about digital campaigning at the state level, where resources (and the playing fields) are more limited.

And while there are authors who have explored the digital divide between Democrats and Republicans, few have taken a deep look at a state-level race to see how rival campaigns have differed in their uses of data and digital technology.

To explore the different ways that the Burr and Ross campaigns took advantage of 2016’s advanced digital landscape, I went behind the scenes – I spoke with people from both campaigns, dug up data, and analyzed their social media content. What I found is that tech-savvy, data-driven campaigning isn’t just for presidential candidates. Congressional hopefuls are investing in tech now, too.

Election 2016: One for the books (and Facebook, Twitter, Instagram, and Snapchat)

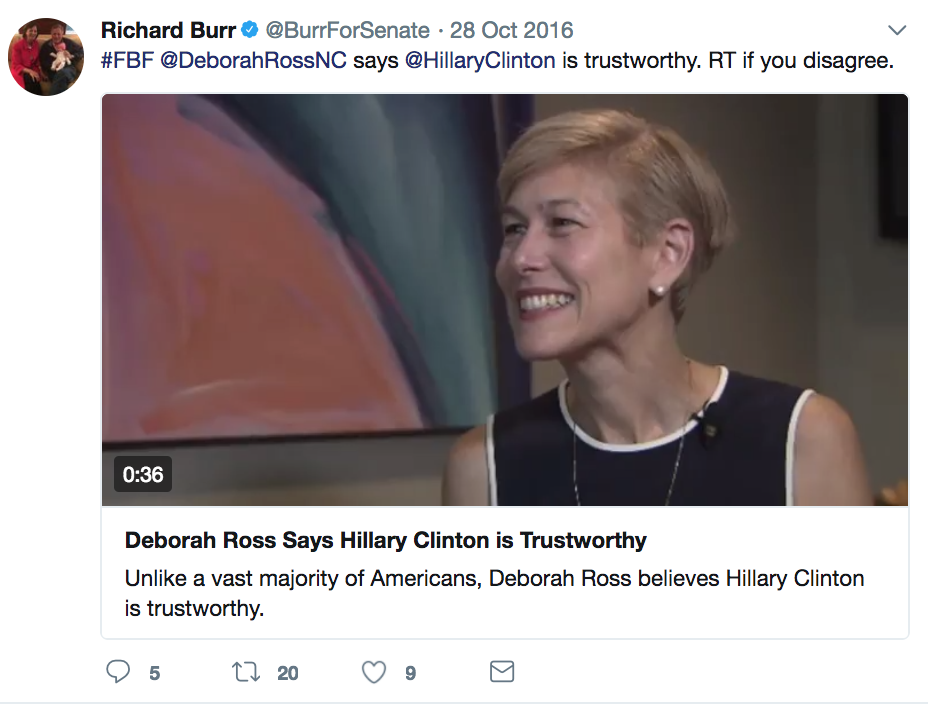

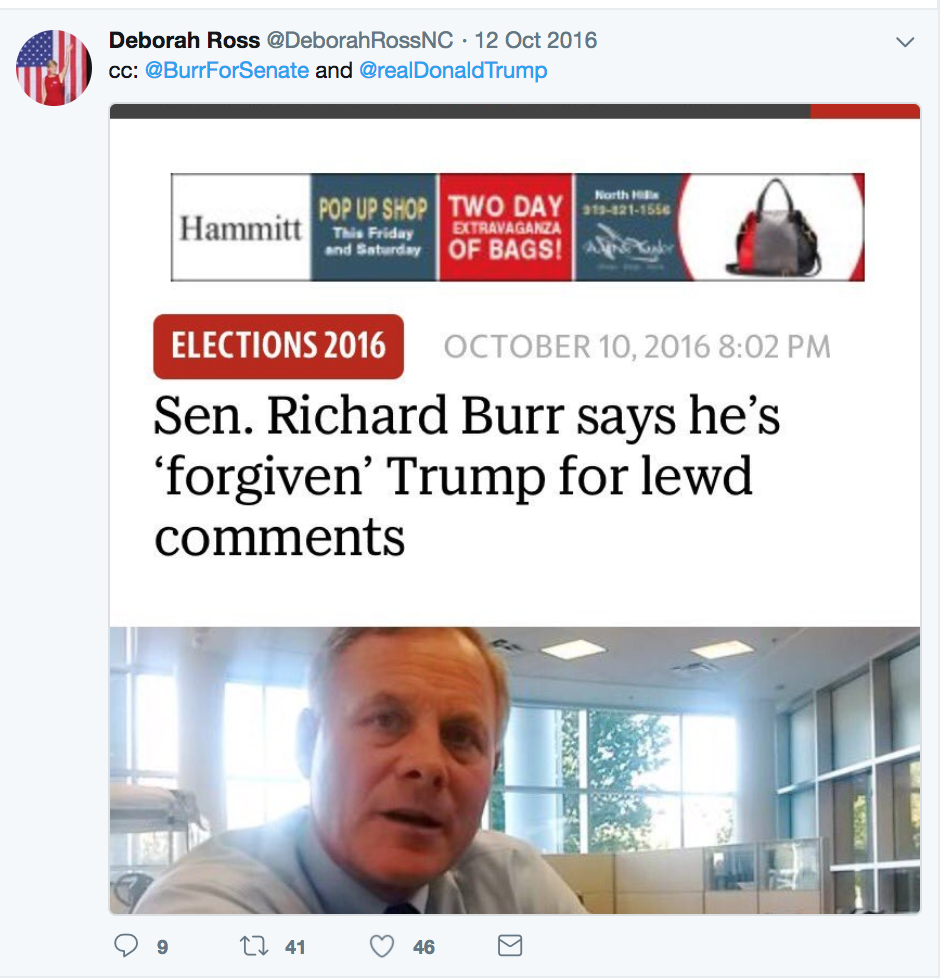

The 2016 election cycle dealt a strange hand to those running for office. The political arena seemed to be turned on its head, especially once Donald Trump and Hillary Clinton’s names were secured at the top of the ballot. Lifelong Democrats were planning to vote for Trump. Well-known Republicans were coming out for Clinton.

At the state level, North Carolina was divided over topics such as House Bill 2 (HB2), more commonly known as “the Bathroom Bill,” which prevented transgender people from using government-run bathrooms corresponding to the gender with which they identify.

North Carolina was one of the most pivotal battleground states during the 2016 election. One of the swingiest swing states, North Carolinians voted for Obama in 2008 then Romney in 2012 – and the state’s 15 electoral votes were a must-win for Trump. It was also a state the Republicans were counting on to maintain their Senate majority.

The two major candidates running for Senate in the state were Republican incumbent Richard Burr and Democratic challenger Deborah Ross. Burr had been serving in the Senate since 2005, and spent a decade representing N.C.’s 5th Congressional District in the House before that. Ross’ political experience included five terms in the N.C. House of Representatives and leading the North Carolina chapter of the American Civil Liberties Union (ACLU) in the 1990’s.

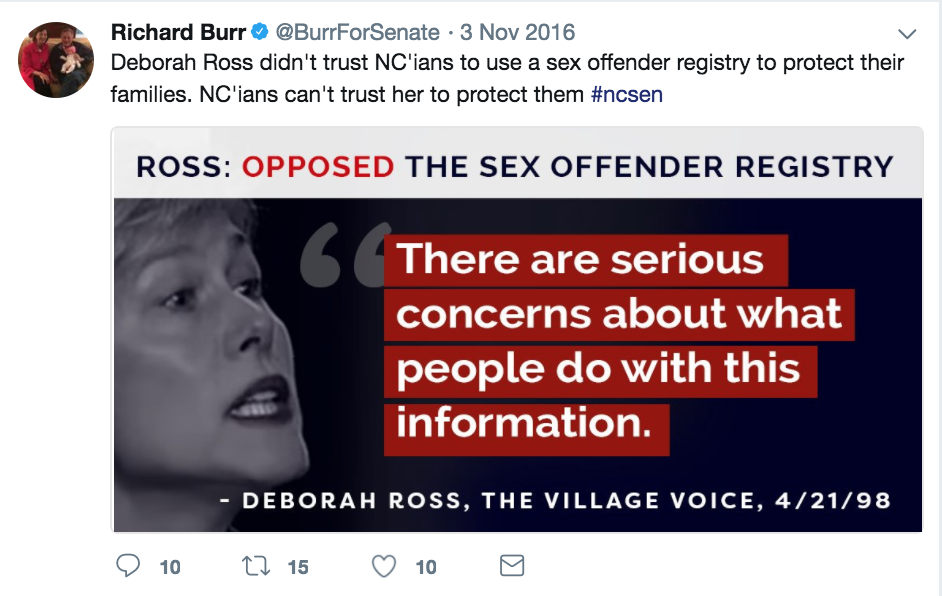

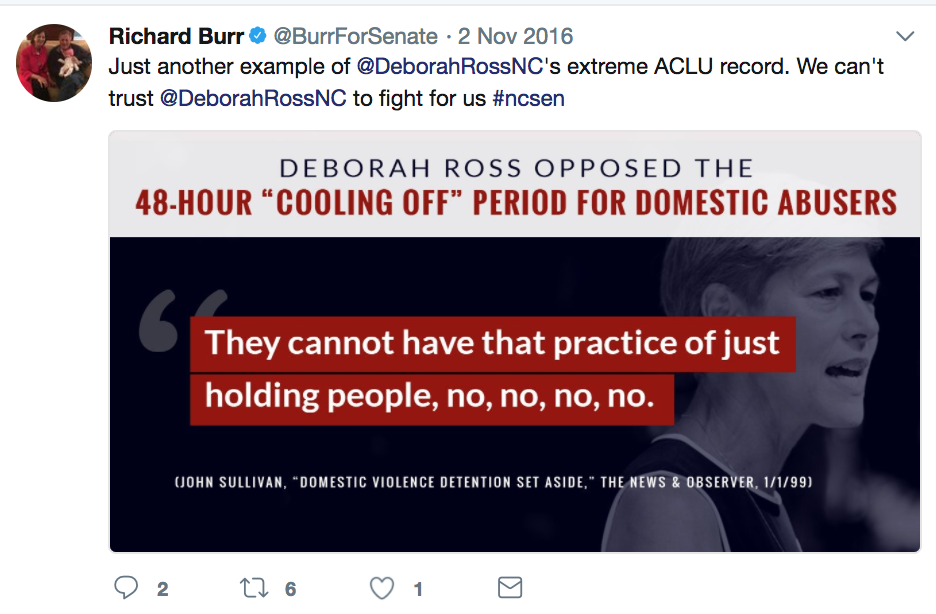

Perhaps the most memorable part of the race that seemed to overshadow the “real” issues was the he-said, she-said fight over Ross’ actions regarding legislation that would place sex offenders in a public database. Burr sponsored ads across virtually every platform that accused his opponent of opposing the sex offender registry. Ross responded with her own ads rebutting Burr’s claims, saying that she had actually fought to strengthen the sex offender registry.

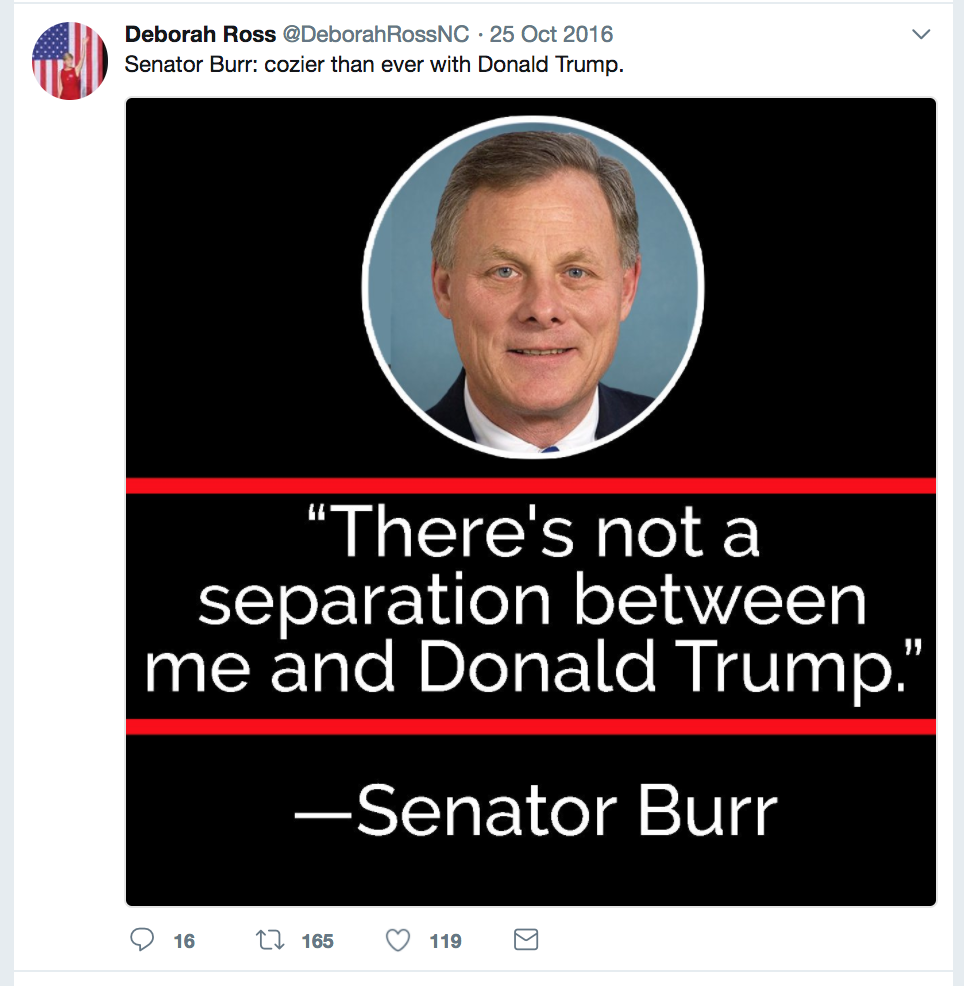

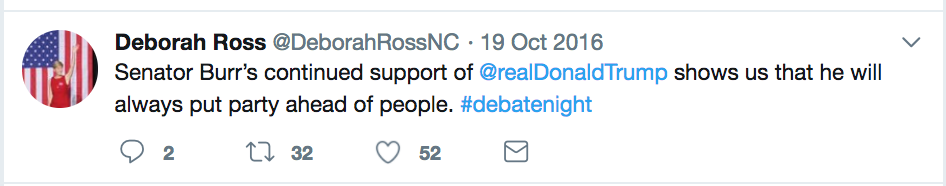

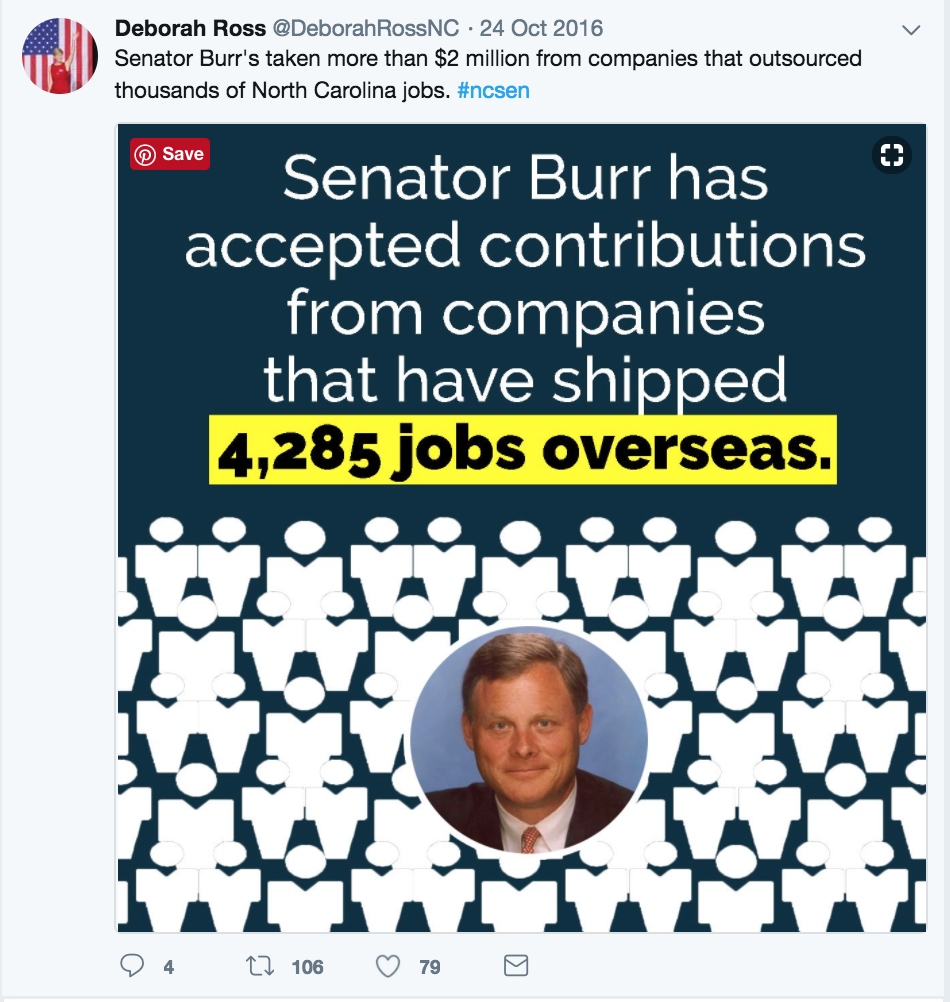

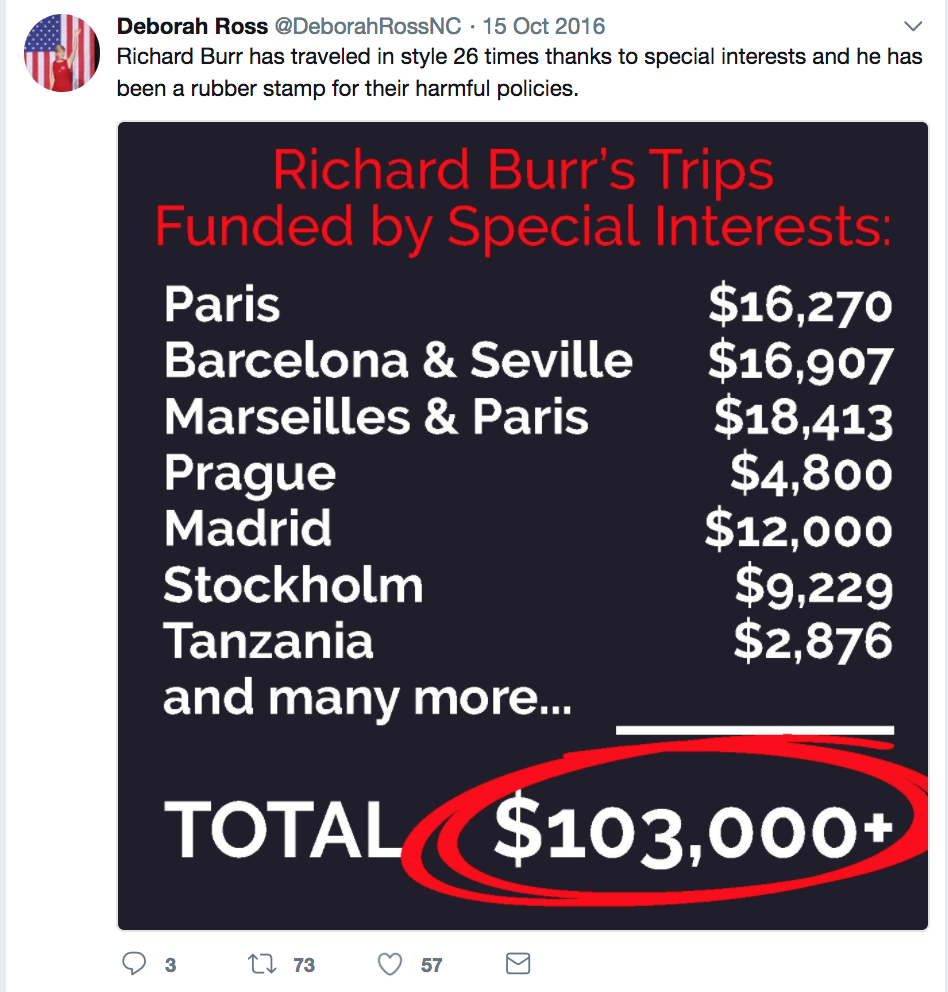

Burr’s campaign pushed the sex offender registry issue hard, along with reminding voters of Ross’ background with the ACLU, trying to paint her as “too liberal” for North Carolina. Meanwhile, Ross’ campaign was showing Burr as a self-interested politician who was more interested in taking private money than in creating positive change in Washington. The race got close, it got dirty, and it got expensive.

Outside groups alone spent more than $58 million to influence the race – much of it going to Burr and Ross’ attack ads that bombarded North Carolina voters in the last few months of the race. That outside-spending total is especially surprising considering that the Ross and Burr campaigns raised a combined $23 million themselves.

But at the end of the day, what both campaigns needed were votes – which meant motivating voters. Many of these voters were most concerned about the state of the economy. Some were focused on terrorism. Foreign Policy. Health care. Gun control. And there was one thing that almost every one of these voters had in common: their use of the internet and digital tools made them (and their data) accessible for these political campaigns.

For those running for public office, the United States’ addiction to the internet and digital media meant there were more ways to reach potential voters – to gain name recognition, to fundraise, to discredit their opponent – than ever before. In a country that is somewhat disinterested in politics (with a low voter turnout, by international standards), connecting with the electorate online gives candidates a captive audience. Meeting potential voters where they already are – on their screens.

In November 2016, 4.7 million people voted in the state of North Carolina. An estimated 90% of those (4.2 million) voters regularly use the internet. Over three quarters (77%) of them own smartphones, and 76% subscribe to paid TV service at home. A large majority – about 69% of them – use social media, and most check their email multiple times a day.

This electorate in 2016 was dramatically more connected than ever before. Virtually all potential voters regularly entered the digital arena in one way or another – and every time they did, they offered campaigns another chance to grab their attention.

And while the rapid advancement and increased adoption of digital technology was offering political candidates new and improved ways to get information to their audience, it simultaneously provides campaigns more advanced ways to get information from their audience.

Taking advantage of large-scale voter data, campaigns (working with data vendors) know more and more about the people whose vote they’re trying to secure. They know all about our lives – our interests, our histories, and our values. They use advanced data models to target individuals with personalized messages. Their messages can be strategically placed and constantly measured.

Both Richard Burr and Deborah Ross built teams that understood the power of these tools and weren’t afraid to use them. The two teams, though slightly different in their approach, were able to use technology and data to garner support, raise money, and ultimately, to secure votes.

These campaigns were run by people who were not only using their own experience to make decisions, but who were also constantly looking for ways to measure the success of those decisions. They listened to each other, but also listened to their data. They followed the money. They pivoted and attacked. And in doing so, they learned some important lessons, and they shared those with me.

In researching these campaigns, I learned three big things:

- Even as social media and digital campaigning become more important, elections are still won on TV. TV ads are still what moves the needle.

- Emails drive fundraising, especially in terms of small-dollar donations

- Senate campaigns are beginning to invest in social media and data technology tools, but they haven’t reached national levels yet.

But there is much, much more to be learned from these campaigns.

While both the Ross campaign and the Burr campaign utilized Snapchat, Burr’s approach strategy was quite aggressive, while Ross’ was much friendlier and laid back.

While both the Ross campaign and the Burr campaign utilized Snapchat, Burr’s approach strategy was quite aggressive, while Ross’ was much friendlier and laid back.