LITERATURE REVIEW

In order to better understand how the Richard Burr and Deborah Ross campaigns use of digital media and data compares to overall national and international trends, this literature review provides background on the current state and recent history of digital technology in political campaigning.

David Karpf, whose research focuses on the internet’s impact on political associations, noted in 2013 that the study of the internet and American political campaigns was still a “nascent subfield.” The literature, he said, “remains in the early, preparadigmatic stages of development” (Karpf, 2013). In the time since, scholars and journalists have added to this field of study, but publications can barely keep up with the changes in digital tools and advancements in technology.

As noted by Gibson, Römmele and Williamson in 2014, the addition and advancement of new “web 2.0” and social media tools continually raises the bar on the extent of interactivity that campaigns could and should involve. For these reasons, many of the following studies and their conclusions should be considered in terms of the date and context in which their research was performed.

Today’s political campaigns and the shift toward technology-driven strategies

In his 2016 book, “Prototype Politics: Technology-Intensive Campaigning and the Data of Democracy,” Daniel Kreiss describes the past decade’s shift toward “technology-intensive” campaigning and the implications that shift has had on politicians, their campaign staff and their potential voters. Kreiss argues that today’s political campaigns have entered a new era when parties and candidates invest significantly in technology, digital media, data, and analytics both to keep pace with the increasingly complex communication environment and to “actively shape technological contexts and define what twenty-first century citizenship looks like” (Kreiss, 2016).

The history and analysis in “Prototype Politics” identifies four major categorical factors driving technological innovation in electoral politics. First, there are structural electoral cycle factors, which include features of the political environment and the broader electoral context at the time of the campaign. This includes variables such as the party currently in power and the state of the economy, as well as the current state of media and technology.

The second category is organizational factors, which include campaign staff, and their cultures and structures. To foster innovation, campaigns must be willing and able to hire staffers from outside the political field, such as in experts from the tech and commercial sectors.

Third comes resource factors – the cash and manpower that campaigns and parties are able to devote to technological development and innovation, supporter recruitment, and the timing and structuring of these resources. Campaign resources are largely determined by electoral context, candidate features, and established infrastructure such as staffer expertise and databases of donors and volunteers.

The final major factor is infrastructure, which Kreiss writes, “form the background contexts that campaigns take shape within.” This includes the party network technologies like field tools and voter files, which can be used to innovate further. They also include the outside organizations (consultancies) that campaigns can hire for their technologies and expertise, and the digital media resources that parties create over time, such as the accumulation of email lists that help support a small-dollar donor culture. Such factors play a role in shaping the campaign’s resources and organizational factors – for example, how a campaign uses technology in its electoral strategy (Kreiss, 2016). Components of all four factors are explored throughout this literature review.

The internet’s failure to make people more political

David Karpf has described the internet of today as a world where anyone can speak, but where only a small elite can be widely heard. He explains that this phenomenon is, in part, due to what he calls the “Field of Dreams fallacy” – a theory that new platforms for widely-adopted citizen participation will ultimately fail because there is no burgeoning online community demanding these tools. If you build it, that does not guarantee that they will come. Digital government initiatives and calls for online political participation rarely flourish, not because the political elites and organizations are resistant to them, but because our citizenry is largely indifferent when it comes to politics (Karpf, 2013).

Scholars have found that, at the mass behavioral level, the internet has not changed historical fundamental participatory inequalities in politics and in the political sphere. Even with the endless amount of participatory avenues found online, research has found that digital tools have done little to shift the inequalities, in terms of political participation, that have existed in American politics. In 2013’s “The Unheavenly Chorus: Unequal Political Voice and the Broken Promise of American Democracy,” authors Kay Lehman Schlozman, Sidney Verba and Henry E. Brady note that, in this connected age, the wealthy, white and well-educated are still more likely to engage online than other segments of the American public.

Using online political activity to predict in-person political activity

That same year, Bruce Bimber and Lauren Copeland explored whether online political activity is consistently related to in-person political activity. Up to that point, research had generally assumed that if such a relationship exists, it would be stable over time and across studies.

Using 12 years of American National Election Studies (ANES) data from 1996 to 2008, the authors found that voters’ amount of online political activity has not been consistently related to traditional acts of political participation. Traditional acts included voting, displaying political messages, attending political events, doing campaign work, donating money to campaigns and persuading others to vote.

This study showed us that use of the internet for political reasons cannot act as a predictor for how likely a citizen is to take part in a traditional political act. Notably, there was the least amount of consistency between online political activity and the acts of 1. voting and 2. donating money (Bimber and Copeland, 2013). This finding tells campaign leadership that, just because someone seems interested in their candidate online, it doesn’t always mean they’re going to go out and vote for them. At the same time, it tells campaigns that their donors may not always be the most vocal online.

More recently, a 2016 study by Jessica Feezell explored the question “What factors predict online participation, and what role does selective exposure play in this relationship?” Feezell was able, through her study, to build on – and in some ways, refute – some of the conclusions made by Schlozman, Verba and Brady. She showed that online political participation and traditional in-person political participation could not be predicted by the same demographic factors. That is, where traditional political participation (and internet use, for that matter) can be related to age and income, that’s not exactly the case with political participation online. Feezell found that those who partake in online political activity are more likely to be ideologically committed, educated and male (Feezell, 2016).

How Democrats use the internet vs. how Republicans use the internet

It is also worth noting that there appears to be a difference between Republicans and Democrats in terms of the how they use the internet for political reasons. Jessica Feezell’s 2016 study found that reported exposure to political information that shares the user’s point of view (selective exposure) is associated with higher levels of online political participation.

However, Feezell also found that Republicans are more likely than Democrats to report seeking political information online that shares their point of view. That is, they are more prone to selection bias. On the other hand, when the reference category was changed to information that differs from one’s point of view, Feezell found that Democrats are more likely to participate at a higher level (Feezell, 2016).

Additionally, Feezell found that Republicans who identified as “ideologically extreme” and/or of Hispanic heritage reported higher levels of online partition. Conversely, she found that Republicans who are female, married, and/or identify as “of mixed ethnicity” are less likely to use the internet for political reasons. These findings confirm for us that the factors that we should use to predict in-person political behavior do not fall in line with the same demographic determinants used in in-person political activity.

The increasing importance of campaigns going online

While online media have not yet overtaken traditional forms of campaigning (especially TV ads) in efforts to mobilize voter turnout, producing digital content is becoming an increasingly important tool to foster campaign participation. In 2016, a team of scholars in the United States and United Kingdom set out to explore how digital tools were changing the extent, nature and effectiveness of political campaigning.

This study, performed by researchers at Duke and Stanford Universities in the U.S. and the University of Manchester in the U.K., concluded that offline forms of campaign messaging still remain more effective in mobilizing voter turnout, a trend most pronounced in voters aged 35-54. However, the study also found that online messages – which directly reach one in five voters – are important in driving campaign participation, especially in younger citizens. These messages are especially effective when they are mediated through their own online social networks. Bottom line: people are more receptive to political messaging when it comes from a friend (Aldrich, Gibson, Cantijoch and Konitzer, 2016).

These findings also suggested that the internet is driving a “two-step” flow model of voter communication – engaging them first through social media, and then offline – which is presenting new opportunities to reach younger potential voters, who have typically been viewed as less politically engaged (and less likely to vote). Those under age 35 were significantly more likely to vote than those aged 35-54 if they received political digital messages from friends and family.

The internet’s information overload makes it easier to ignore politics

Though it may seem counterintuitive, the abundant sources of information that continually become available to online consumers have only made them more indifferent. Markus Prior’s research on the media preferences of U.S. citizens demonstrates that, when consumers move from a low-choice environment (network television) to a high-choice environment (cable television), there are tremendous unintended negative impacts on political participation and knowledge.

Years ago, in the age of network-only TV, even citizens who did not actively seek out political knowledge were exposed to some amount of political information when they turned on the evening news. This put them on about the same level, information-wise, as those who craved more detailed political information, but who, because of limited channels and choices, did not have the multiple avenues to indulge those cravings as we can today, with our endless amount of TV channels, websites and social media streams.

Then cable TV came along, with its hundreds of channel choices, and the “news junkies” could now watch CNN, Fox News, MSNBC and many others – but the politically disinterested viewers could flip the channel to ESPN or MTV and remain both indifferent and uninformed. Prior argues that, as more media channels become available through television, the internet and social media, this gap will continue to widen, and it will become increasingly easy to change the channel, open up a new app, and turn a blind eye to the political world (Prior, 2007).

TV it’s still #1 in campaign ad spending – and it’s getting smarter

While digital strategy is becoming more and more important in delivering messages to voters, television continues to eat up the bulk of campaigns’ advertising budgets (Willis, 2015). Even while many people are “cutting the cord,” and favoring digital content over traditional network and cable TV, 87% of Americans of voting age still watch television, according to a 2015 report by Nielsen. This report shows that television-watching adults spend a staggering 7.5 hours a day in front of a TV set. That’s far more time than people spend watching content on their computers, smartphones or tablets, which adds up to about 3.6 hours per day, combined.

Even more notable for those using this data to plan campaign ad spending is that older Americans (the most dependable voters) watch more television than younger Americans (The Total Audience Report, 2015). Campaigns are now able to make sure they reach these TV-watchers using “programmatic TV” to efficiently spend their cash. With programmatic TV, voters can be targeted either through certain television programs, or even as individuals.

For example, data management services like Deep Root Analytics helped the Trump campaign identify “NCIS” as a popular show among people who had negative feelings toward the Affordable Care Act, and “The Walking Dead” as a show that was watched by many people who favored strict immigration laws. “Older Republican primary voters also watch a lot of ‘Law & Order’ reruns,” said Scott Tranter from Optimus, an analytics firm that has been hired by Republican campaigns (Bertoni, 2016).

Political campaigns have been a driving force of innovation in targeting TV viewers. “A lot of times, there is inertia [in TV marketing] that you keep doing things the way you have done things,” said Brent Seaborn, founding partner of Deep Root Analytics. “But politics is different. The campaigns are temporary and extremely competitive, which forces a lot of innovation and a different tone.”

The voters, and thus the TV programs, that campaigns want to target change throughout an election. “During most of a campaign, you want to target persuadable voters,” said Ken Strasma, CEO of HaystaqDNA, which assisted in media planning for both the Obama 2012 and Sanders 2016 campaigns. “Later on, you want to target your likely supporters to get them to turn out and vote” (Benes, 2017).

There are two types of targeted ads: addressable and predictive. Addressable ads target specific individuals; predictive ads are shown to a given market, but those ads are singled out by political groups based on probabilities that their key voters will watch that program (like the “Walking Dead” and voters who want strict immigration laws). While addressable advertising has become more common for political campaigns, it’s expensive.

So rather than spend the money on addressable ads, analytics firms like HaystaqDNA and Deep Root Analytics work with data to inform campaigns which programs would be most effective to target their desired voters. Paired with commercial data, these firms can help campaigns create more complete voter profiles, which analysts then use to build models that can more accurately predict the likelihood of a specific voter turning out, or how likely it is that the voter will vote against their registered party (Benes, 2017).

So far, these companies haven’t yet mastered how to use social media data to improve their TV targeting practices. “Unfortunately, as it stands now, the number of people whose identities we could match and who also had addressable TV was too small to make it practical,” said Ken Strasma.

Online ads are beginning to close the spending gap with TV

As noted earlier, TV is still king in campaign advertising. But a new report from research firm Borrell Associates, a group that tracks ad spending, shows that trend may not continue forever. Their analysis shows that while 2016 was a record year for campaign ad spending (up 4.6% from 2012), there were changes in how those billions were spent. Compared to 2012 spending, the biggest beneficiary of this spending – TV – was left with $1 billion less, and the smallest – digital media –gained $1.2 billion in spending.

These numbers represent a nearly 5,000% increase from what was spent on digital ads in 2008. By 2020, it is predicted that spending on digital media alone will increase to nearly $3.3 billion. This will still fall behind TV ads, which currently cost campaigns $8.5 billion, but experts predict that the gap will continue to shrink (Lapowsky, 2015).

Online and social media apps give users a new way to engage

Applications (“apps”) available online or through social media can help candidates and lawmakers “foster a genuine involvement in the legislative process,” said Matt Lira, who served as Director of New Media in former House Majority Leader Eric Cantor’s office. Cantor, a Republican from Virginia, created a Facebook app called Citizen Cosponsor, which allows users to follow bills as they move through the legislative process.

Similarly, the Obama White House created an app called We the People, which allows users to create and sign online petitions (CampaignTech Panels, 2012). “Both We the People and Citizen Cosponsor are designed so that you not only receive information about what the updates are, but you’re given continual opportunities to engage in the legislative process,” Lira said at the 2012 CampaignTech Conference. These apps help to create a two-way model of communication with constituents, and keep voters involved once campaigns are wrapped up.

“Friending” the voter: Campaigns and direct interaction with constituents

Campaigns with an online presence should not ignore the “social” part of social media, according to Katie Harbath, a public policy manager with Facebook. “We highly recommend that you encourage comments,” she said. “I know that can be scary for a lot of campaigns. But [by] allowing a discussion to go on, you’re going to have a lot more traffic and vibrancy on the page than if you try to have it all just be positive content, or not really much discussion” (CampaignTech Panels, 2012).

Strategists also say that candidates are most successful when they customize their message for each social media platform, and when they respond quickly. “I think depending on the platform you’re on, you need to be either more playful or clever,” said Marie Danzig, a former Obama staffer who leads creative and delivery for Blue State Digital. “You need to operate more quickly on Twitter than you do on Facebook. I think Snapchat and Periscope will continue to become more of the norm in terms of providing behind-the-scenes content (McCabe, 2015).

According to Michael Jensen, however, campaigns are not fully taking advantage of their ability to interact directly with their constituents on social media. Using data from the 2015 U.K. general election, Jensen developed a way to analyze the structure of campaign communications within Twitter, and investigated the social relationships formed by political campaigns and their supporters that occur there. He identified three categories of empowering messaging that can occur on Twitter: 1. Campaigns responding to others, 2. Campaigns re-tweeting others’ content and 3. Campaigns calling for people to become involved in the campaign on their own accord.

Jensen’s evidence revealed little effort and involvement by political campaigns to empower campaign supporters. While there are now so many ways for campaigns to interact socially with voters, results showed that direct calls for participation are limited, and the direct empowerment of citizens is very selective. Replies to citizens comprised a very small portion of the tweets from a campaign; and when candidates do re-tweet another user, it’s a message that uses the same policy terms that the campaign uses (Jensen, 2017).

Daniel Kreiss described the use of digital media by campaigns as “a story of institutional amplification, not necessarily democratic revolution.” The internet’s newest tools have greatly amplified some forms of political collective action, he says, in institutionalized contexts. Campaigns use digital media to make it easier to contribute to their cause online, and to give supporters more opportunities to volunteer by organizing events, phone banks and fundraising online. What new media has not been able to do, says Kreiss, is “to make campaigns more responsive to their mobilized supporters outside of the generally shared ends of getting a candidate elected” (Kreiss, 2015).

The 2016 Election: True Digital-First Campaigning

From the beginning, the 2016 election was in large part driven by social media, as candidates from both major parties saw Facebook, Twitter and Instagram as important battlegrounds in the race for the White House. While previous campaigns had used social media, this was the first time that social media threatened to overtake traditional outlets (TV, paid ads) as the top venue for candidates to gain attention (McCabe, 2015).

The Bernie Sanders campaign, for instance, translated Sanders’ huge social media following and the power of the #feeltheBern hashtag into record-breaking attendance at his political rallies. Likewise, Donald Trump easily gained the attention of his 4 million followers with one late-night tweet. In fact, according to the data-driven analytics firm mediaQuant, Trump received an estimated $5 billion in free media coverage, which was driven in part by his constant stream of headline-making statements on Twitter.

Early on in the campaign, social media had also become a virtual stage for debate, with candidates facing off in a way that we had never seen before. In August 2015, Hillary Clinton and Jeb Bush went back and forth on women’s health issues, and then again on college affordability. “I think one of the most interesting things this year is that it’s no longer a question of if candidates should be using these platforms, it’s how and how often,” said Erin Lindsay, a principal for digital at Precision Strategies, a consulting firm founded by veterans of Obama’s 2012 campaign.

The 2016 election was arguably also the first election to think digital-first. Ted Cruz, the first contender to throw his hat into the presidential race, announced his campaign with a tweet just after midnight on a Monday morning in March 2015. The message simply read “I’m running for President and I hope to earn your support,” and included a link to a 30-second video. He didn’t announce his candidacy at a big rally, and then post that to Twitter – his tweet kicked everything off. Digital-first.

“[Social media] is where you’re going to set the tone for your messaging,” said Will Ritter, advance director for the Romney 2012 campaign and co-founder of the digital strategies firm Poolhouse. “It’s about marrying the fresh platforms with an old rule: get to people where they are” (Simendinger and Huey-Burns, 2015).

One prime example of a candidate merging old platforms with new technology was when Jeb Bush broadcast his speech at an Atlanta fundraiser using a live-streaming app called Meerkat, which allowed him to invite his 170,000 Twitter followers to virtually “attend” his speech in real time. However, only about 400 of his followers and a few political reporters tuned in.

Nothing in the 2016 election cycle was to be unmeasured, untested, untargeted or static when it came to mobilizing voters. If a campaign website page was blue and the “donate” button was red, for instance, there were metrics behind those choices (Simendinger and Huey-Burns, 2015). Strategies for digital outreach – presidential candidate announcements, generating national and local news media, seeding grassroots interest, attracting donations – were constantly informed and shaped by digital data.

The political battleground in voter’s pocket: smartphones and campaign mobile strategy

According to the Pew Research Center, about 77% of Americans own smartphones. Smartphone ownership has more than doubled since the Center began surveying in 2011 (that year, 35% of Americans owned a smartphone). For this reason, candidates ramped up their mobile messaging strategy for 2016. “Everyone is implementing mobile solutions right now,” said Larry Huynh, partner at Trilogy Interactive, a digital consultancy for political campaigns and advocacy groups. Campaigns that aren’t using mobile technology to reach voters “are doing it wrong,” Huynh said (Vega, 2015).

Unlike what a user sees on a desktop computer, mobile display ads often take up the entire screen of a mobile device, said Andrew Lipsman from the digital analytics company comScore. This makes users more likely to click on the ad. “Ads tend to be more effective in mobile,” said Lipsman.

Mobile devices also offer campaigns new forms of voter data, such as potential voters’ geographic locations and what websites they have visited. Campaigns can use such data to target specific groups of desired voters with specific messages. Likewise, the same technology could be employed to send messages to people who have downloaded the candidate’s app, or who are currently attending one of his rallies (Vega, 2015).

Negative vs. positive messaging on social media

Few studies have looked at the actual content of campaigns’ political messages on social media, but one study from scholars in Italy investigated the effectiveness of positive and negative messages during the 2013 Italian general election. Measured through an innovative technique of sentiment analysis using content published on the official Twitter accounts of the Italian political parties, Andrea Ceron and Giovanna d’Adda evaluated the impact of both positive and negative tweets. Their results showed that when one party tweets out negative content attacking its rival, there is a positive effect on the tweeting party’s share of voting intentions – that is, attacking the rival party increases the support for the attacker.

Moreover, they found that the more a party is subject to attacks from other parties, the higher the returns from negative campaign tweets. This falls in line with expectations from social psychologists who have discovered that negative messages can often persuade more than comparable positive messages, and the assumption that negativity can generate fear, which drives interest in political campaigns. Conversely, results revealed only a circumstantial effect of positive campaign messaging released via Twitter (Ceron and d’Adda, 2016). The mobilization effect is particularly relevant in the context of social media platforms like Twitter, given their nature to create “echo chambers” as users’ timelines are fed with media sources whose views fall in line with their own.

How social media users react to their networks’ political messages

Though an echo chamber effect is often found on social media, a 2012 survey by the Pew Research Center’s Internet & American Life Project found that birds of a feather don’t always flock together on social media sites. The survey, distributed to over 2,000 citizens of voting age, found that friends often disagree with friends about politics, and usually let such disagreements pass without comment. Of those surveyed, 73% of social network users “only sometimes” agree with or never agree with their friends’ political-related posts. The majority (66%) just ignore these posts, with only 28% reporting that they “usually respond” to posts with which they disagree with their own comments or post (Rainie and Smith, 2012).

The Pew Internet Project found that 80% of adults use the internet, and about 70% of those adults use social media. Of social media users, 75% reported that they have friends who post political content on social media, and 37% of users surveyed said that they post political messages themselves. These results suggest that, like other Americans, social media users in the U.S. are not particularly passionate about politics. (Rainie and Smith, 2012). Likewise, the results show that many social media connections are not centered on political discussion. Perhaps politics have not gained popularity on social media to the same extent as other areas of conversation because, as David Karpf said, our citizens are uninterested.

Of course, there are some users who are particularly passionate about politics, and their social media activity reflects that. The Pew study found that 16% of social media users have friended or followed someone because of that person’s posts of a political nature. Conversely, 9% of social media users have blocked, unfriended or hidden a social media connection because they posted political content that they disagreed with.

“Shunning” is more frequent among those who identify as liberal, with 28% reporting that they had removed a friend for those reasons, compared with 16% of conservatives and 14% of moderates. Liberal social media users are also more likely to have friends who regularly discuss politics on social media (38%) compared to conservatives (25%).

Additionally, this study found that 47% of social media users have “liked” political comments or material posted by someone in their network, and 38% have posted positive comments in response to a friend’s political post. Finally, the study found that for some users, politics is an off-limits subject on social media. Some 22% of social media users reported that they do not post political content on social media in order not to offend people in their social network (Rainie and Smith, 2012).

Social media and down-ticket races

While most of the literature that exists on these subjects focuses on presidential elections, some authors have looked more closely at congressional elections. A 2012 study by researchers from the Political Science and Psychology departments at the University of California San Diego showed that political messages delivered on Facebook during campaigns directly influenced political behavior. The UCSD researchers used a randomized controlled trial of political mobilization messages delivered to 61 million Facebook users during the 2010 U.S. congressional elections. They found that those messages had a positive influence on political self-expression, political information seeking, and actual voting behavior (Bond et al., 2012).

Additionally, these political messages also affected the behavior of users’ friends, and their friends-of-friends. This effect of social transmission via Facebook was greater than the direct effect of the messages themselves – nearly all of the transmission was between “close friends,” or those who they were more likely to have an offline, face-to-face relationship with. The people who received the message from a friend, rather than receiving it directly from the campaign, were more likely to vote in real life. These results suggest that messages that include a social element from a real-life friend or acquaintance are much more effective, in terms of mobilization, than the information-only message (Bond et al., 2012).

Kim, Painter and Dunton Miles studied the 2010 cycle– specifically looking at the gubernatorial election in Florida, to find out more about the differential effects of political campaigns’ online strategies and viewers’ emotional responses to the candidates (Republican Rick Scott vs. Democrat Alex Sink) and evaluations of their campaigns. Using 300 college students between 19 and 21 years old, the study showed that candidate websites may influence viewers’ perceptions of the election’s importance more than the campaigns’ social networks do.

At the same time, results showed that the impact of online interactivity on viewers’ emotional responses to the candidate is greater on social media channels (Kim, Painter and Dunton Miles, 2013). These findings suggest that it is important for campaigns to put resources into both their website and their social media presence. It also reinforces the importance of actively promoting both website and social media content, displaying links to the candidate’s social media accounts on their website, and vice versa.

Political candidates and the online popularity contest

While political campaigns and their candidates vary greatly in terms of website traffic, Facebook friends, and Twitter followers, little is known about what drives a congressional candidate’s online popularity. In a 2013 article, Cristian Vaccari and Rasmus Kleis Nielsen address this question by comparing the popularity of candidates across 112 of the most competitive congressional districts in the 2010 U.S. midterm elections. Using multivariate ordinary least squares regression models, the authors were able to identify two factors as being significant in terms of driving candidate popularity: 1. a candidate’s distance from power – that is, challengers and those running for open seats do better than incumbents, and 2. how intensely the candidate is discussed in the top political blogs.

The trend that challengers, open-seat candidates, and those from the party out of power (Republicans in this case) were consistently more popular online than other candidates stands in contrast to almost all other aspects of contemporary Congressional campaigns in which factors such as endorsements, fundraising, and news media coverage all tend to favor incumbents. Online platforms, the study concluded, do not offer an “incumbent’s advantage.”

Other factors that may be expected to play a part in online popularity, such as the candidate’s district-level variation in income and education or the volume of coverage that the candidate receives from traditional media outlets, had very little effect. Some other potential predictors, such as the amount of campaign resources, or a candidate’s standing in polls, seemed to effect popularity only on Facebook, and not on other social media platforms (Vaccari and Nielsen, 2013).

Balancing digital tools and traditional campaign messaging

Despite the surge of technology in politics, media experts and researchers agree that computers alone cannot win elections. “If that were the case,” said C-SPAN’s Howard Mortman, “then Howard Dean would’ve been elected president” (CampaignTech Panels, 2012). Campaigns must now strike a balance between old fashioned campaign actions like door knocks and handshakes and this new era’s digital tools like social media.

“There are some people you can only reach through Facebook,” said Jim Gilliam, founder of the online organizing tool NationBuilder, while speaking at the CampaignTech conference in 2012. The new era digital tools, however, may not be as easily accepted by politicians who are used to more old school approaches. “The pattern that you see over and over is new media people that have this great stuff in their heads but can’t get it across to their bosses,” said Leslie Graves of Ballotpedia and Judgepedia.

For many political campaigns, advertising strategies can make the difference between winning or losing an election. “The standard tactic is to raise all the money you can, and pour it into one of two buckets: one labeled “TV” (80%) and one labeled “Other” (20%). While some campaigns seem to be clinging to the TV/Industrial complex of decades past, the experts suggest moving on to a more hybrid model (CampaignTech Panels, 2012).

Using social media and online ads to personalize campaign messages

When you do run ads online, it pays off for campaigns to make messaging as personal as possible. “The more personalized you can make it, it cuts through the clutter,” said Sean Duggan, Vice President of Advertising at Pandora Internet Radio (CampaignTech Panels, 2012). For example, Jeb Bush posted a photo to Instagram of a tortoise on the lawn of the Reagan Library; Marco Rubio gave supporters an “inside look” at his announcement via Snapchat; and Scott Walker would often post photos of his meals, including a slice of sausage pizza at the Charlotte airport (McCabe, 2015).

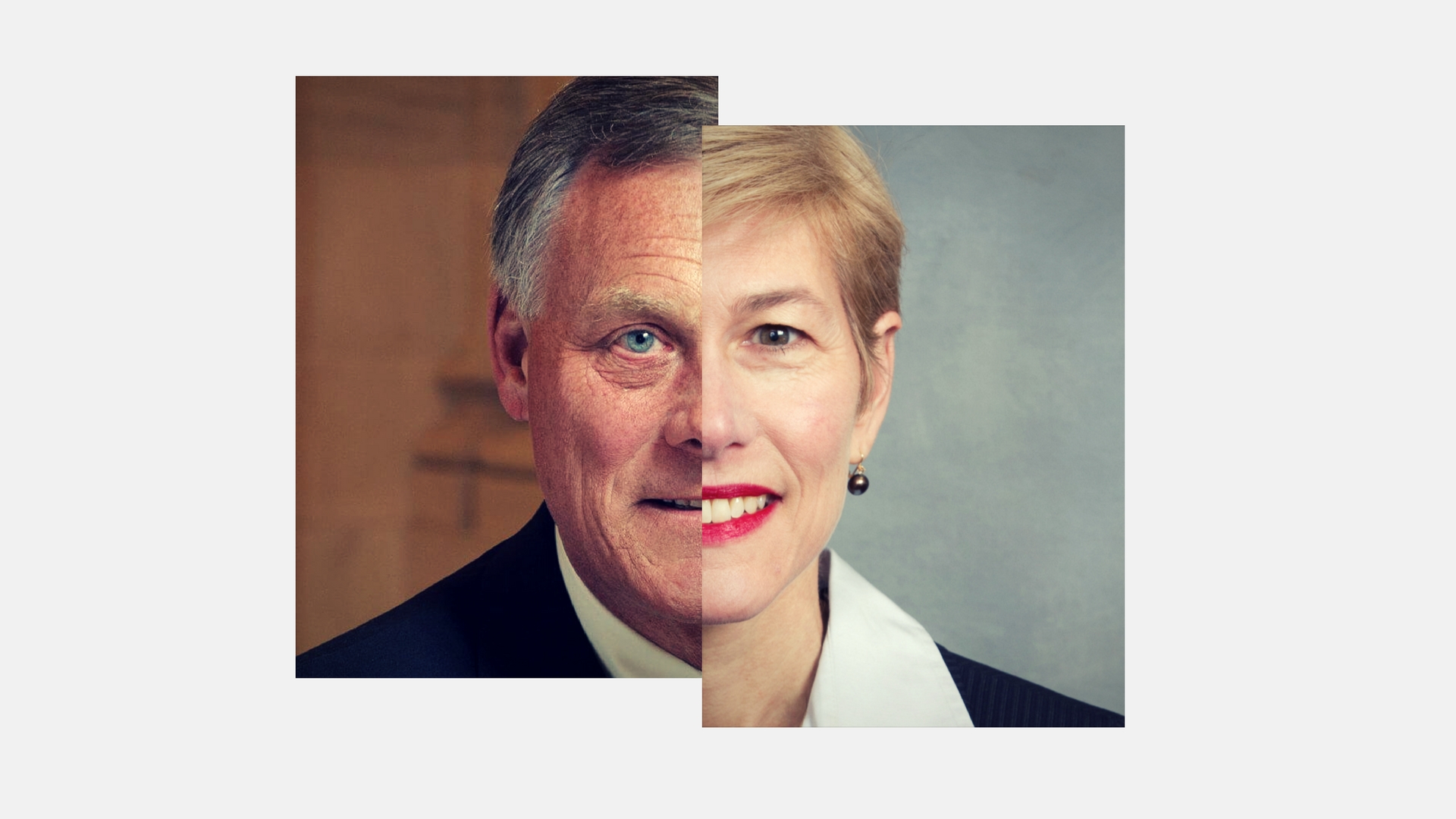

Especially since I will be studying a state-level race between a male (Richard Burr) and female (Deborah Ross), it is worth mentioning a study by McGregor, Lawrence and Cardona that focuses on the levels of personalization in social media messaging among 2014 gubernatorial candidates and how they are affected by candidate gender. A large-scale computerized content analysis of the social media communication of 16 statewide candidates found that personalized communication made up a small percentage (7.9%) of their posted content. Campaigning, on the other hand, comprised about half (50.8%) of all social media messages posted, with candidates talking about policy on social media roughly twice as much as personalizing information (McGregor, Lawrence and Cardona, 2017).

Of course, some politicians (like Scott Walker, who was known to tweet photos of his meals) personalize their social media messages more than others, and according to this study, gender and political party may both play a role in this. Results show that male candidates posted personalized messages more than female candidates; 10.6% of the male candidates’ communications were personalized, versus 5.1% of the female candidates’ messages. There was also a slight difference in how the candidates personalized their messages. While candidates of both genders occasionally highlighted their family (pictures with grandkids, for example), only female candidates shared images of themselves in caregiver roles (cooking, cleaning, doing homework with their kids, etc.).

This model also revealed that Democrats are 32.8% less likely to post personalized communications, and that posts during the primary election period are 42.6% more likely to be personalizing than those posted during the general election. Finally, the researchers showed that the more competitive the race, the more likely the candidate was to post personalized messages – almost 10% of posts from candidates in “toss up” races were personalized, which was more than double the rate among races that were considered “safe” (McGregor, Lawrence and Cardona, 2017).

Could social media be a better election predictor than polls?

Increasing attention is being paid to social media analytics as a useful complement to traditional polling. In 2015, Ceron, Curini and Iacus conducted a sentiment analysis study to analyze the voting intention of Twitter users in both the United States 2012 Presidential Election and the 2012 Italian center-left primary elections. The researchers monitored Twitter from September 8 until November 6, and looked at the voting intentions expressed on Twitter toward the four main candidates (Obama, Romney, Johnson, Stein). They estimated the political preferences of voters on a daily basis through sentiment analysis of 50 million tweets.

Results showed that fluctuations in preferences expressed online closely followed the main events that happened during the electoral campaign. For example, after Obama’s somewhat poor performance during the first TV debate, Romney passed President Obama in the number of Twitter users who were indicating they would vote for Romney. As the campaign drew to a close, the sentiment trended toward Obama. In fact, the researchers’ forecasted that Obama would win with an easy, safe 3.5% margin. This figure was much closer to the actual gap in the share of votes (3.9%) than was predicted by traditional survey polls that, on average, predicted only a narrow margin of victory for Obama (+0.7), and were saying that the race was “too close to call.”

The same sentiment analysis was applied to 11 “swing states” (which included North Carolina). By analyzing the social media activity alone, researchers were able to correctly predict electoral results in nine out of the 11 swing states. Even more notably, their predictions using sentiment analysis on Twitter were more accurate than what the polls predicted in all nine cases. The only two swing states that they were unable to predict better than the polls were Colorado and Pennsylvania (Ceron, Curini, Iacus, 2015). This study highlights the predictive power of social media that could not only be used to forecast the winners of races, but also for campaigns to more efficiently advertise in states where they may be most vulnerable.

David Karpf points out, however, that this method faces some often-overlooked limitations. Not only is most high-quality “big data” proprietary, but most publically-available data has a GIGO, or “garbage in, garbage out” issue. Web links, social media likes and shares, and YouTube views all experience a constant barrage of spammers messing up the data. As an overarching rule, Karpf says, “any metric of digital influence that becomes financially valuable, or is used to determine newsworthiness, will become increasingly unreliable over time” (Karpf, 2013).

“Second Screening” in political campaigns

The simultaneous use of multiple digital tools at once, known as “second screening” or “dual screening,” has changed the way voters around the world consume and discuss political information. One popular time for second screening is during a televised debate; viewers will often follow along on social media platforms like Twitter to fact-check, post reactions and read commentary.

Gil de Zúñiga and Liu performed a study to create a multinational snapshot of citizens’ second screening habits for news and politics. They found that young people, unsurprisingly, second screen more than older citizens. They also saw differences between more intensive second screen users and those who use dual screens at lower levels. The more intensive second screeners tend to politically express themselves more via social media, and are also more likely to take part in offline political activities. However, the results did not indicate a significant difference between the intensive second screeners and the occasional second screeners when it came to actual voting behavior.

In all of the countries studied, second screening in a political context has increased with each voting cycle (Gil de Zúñiga and Liu, 2017). Campaign media planners could help prepare for the events (like debates) and conversations that could lead voters to a second screen.

The internet and campaign fundraising: Supporters and the “Donate Now” button

The rise in online campaigning has brought in a new wave of small-donor fundraising, making it easier to not only acquire donors, but to turn those supporters into repeat donors. In 2012, 69% of Obama’s donors started with a small contribution, many of which were made online. Online donors averaged more than five contributions each throughout the campaign (Malbin, 2013).

Advances in campaign technology have also created room for new avenues of online fundraising and donor acquisition, such as the bundling system for small donor communities called ActBlue. ActBlue.com, alone, facilitated over $400 million in donations to Democratic political action committees between 2004 and 2012 (Karpf, 2013).

Though social media tools may not yet be a popular direct avenue for campaign donations, it certainly helps political fundraisers with donor acquisition, which begins with gathering potential donor information. Facebook’s Katie Harbath points to Facebook applications. “Rather than making people fill in a bunch of field forms to sign up for your email list, they can just click to register,” reported Harbath (CampaignTech Panels, 2012).

Candidates, for example Mitt Romney, have taken advantage of this tool to acquire supporter data for email lists, as the Facebook app automatically fills in the potential donor’s name, email address, location, birthday and gender. Signing up on a candidate’s website, on the other hand, only requires a zip code (CampaignTech Panels, 2012). But it’s not enough just to create an app. “You need to put a lot of effort into marketing them,” said Harbath. “Of the budget you have, 20 percent should go to actually building the app and 80 percent should actually go to promotion the application.”

The Obama campaigns and recent Democratic digital dominance

When it comes to the use of digital data and technology in campaigning, some studies have identified a clear gap between the Democratic and Republican parties in the last decade. Pre-2008, the Republican Party and their consultancies seemed to have some digital advantages. While little has been written about it, the 2004 George W. Bush presidential campaign had the upper-hand in digital media strategy, database integration and field campaign technologies. In fact, Obama’s campaign manager, David Plouffe looked to the Bush campaign’s strategy as a model for Obama (Kreiss, 2015).

At the same time, the Democrats found a strong technical and organizational foundation through the Howard Dean campaign, which reached new heights in online engagement and grassroots fundraising. Out of the ashes of Dean’s 2004 presidential campaign arose 18 individual firms and organizations, which led to continual innovation and the build-up of data that would later be used in Obama’s groundbreaking campaigns.

Democrats created companies like Blue State Digital and Precision Strategies (both mentioned earlier), the Voter Action Network (data that fueled Obama’s campaign data) and the Analyst Institute (for analytics) while Republicans stayed at the status quo (Kreiss, 2016). Because the Republicans were not keeping up with this level of innovation, they “walked into 2008 with a 2004 product,” said Chuck Defoe (Kaye, 2014).

The Democratic Party was investing large amounts of money and resources to produce digital expertise, databases and practitioners. These investments paid off in the Obama 2008 campaign. Obama’s team was able to ignite extraordinary public participation around their campaign, and raise a lot of money, but what helped give them the presidency was that they were able to leverage those tools to mobilize voters. “Mr. Obama used the internet to organize his supporters in a way that would have in the past required an army of volunteers and paid organizers on the ground,” said political consultant Joe Trippi, who ran Howard Dean’s 2004 campaign.

Obama’s re-election campaign built upon the strategies of 2008, namely its “computational management” decision-making style within the campaign. This meant that all decisions relating to management, allocation, messaging and design were informed by the campaign’s multiple data streams. Data were a central component to all aspects of the 2012 campaign, and the Obama team now knew not only how to get data, but how to work with it. For instance, the campaign created statistical models that were able to predict someone’s likelihood to support Obama, and planned their voter contact operation according to those models (Kreiss, 2015).

Williams and Gulati conducted a study to examine the early adoption and dissemination of new digital tools – specifically Facebook – in the 2006 and 2008 U.S. House of Representative elections. In analyzing more than 1,600 candidates from both major political parties, they were able to show that Democrats were more likely than Republican candidates to integrate the use Facebook into their campaign strategy.

The Democrats’ higher level of enthusiasm for the social network seemed to reflect a difference in the two party’s mobilization strategies, as Democrats were more eager than Republicans to use the internet to communicate with supporters. While Republicans were perhaps on the cutting edge of using new technologies such as voter databases to identify their potential voters, their strategists tended to work within top-down organizational structures and tended to rely on communication and mobilization strategies that they had used in the past instead of trying out new tools (Williams and Gulati 2015).

The digital wake-up call heard by Republicans

In the aftermath of the 2012 presidential election, the technology gap between the two major parties attracted a lot of attention. Barack Obama’s campaign in 2008, and even more so in 2012, relied on sophisticated digital data and internet strategies in a way that we had never seen before.

The Republicans took note. The RNC’s Growth and Opportunity Project report, which was created in the wake of their 2012 presidential loss, focused largely focused on changing the party’s image and effectiveness through rhetoric and tactics (Ball, 2014). The report noted Obama’s clear technological advantage in the 2012 presidential election. “Democrats had the clear edge on new media and ground game, in terms of both reach and effectiveness,” said the report. “Marrying grassroots politics with technology and analytics, they successfully contacted, persuaded and turned out their margin of victory. There are many lessons to be learned from their efforts, particularly with respect to voter contact.”

The Democrats had been recently outperforming the Republicans in the digital sphere because for the last decade, they have been investing greater resources into digital strategy and prioritizing digital, data, and analytics more than their more conservative rivals. Kreiss and Jasinski conducted a mixed-methods study of campaign staff employment history, looking specifically at those working in technology, digital, data and analytics on primary and general U.S. presidential campaigns from the 2004 through the 2012 election cycles. Using data from the Federal Election Commission and LinkedIn, they traced the professional biographies, and found differing levels of professionalization in those areas.

Results showed that Democrats had significantly more staffers with backgrounds in technology, digital data and analytics, and who had come from the tech industry. This trend seems to have begun with Howard Dean’s 2004 campaign, as 86% of Dean’s staffers were from industries outside of the political machine. Republicans, by comparison, have since been less likely to hire “tech people” onto their campaigns. Staffers with these skills were notably undervalued during the 2012 Romney campaign, which was more oriented toward traditional media buying (Kreiss, 2016).

While Republicans were relying on gut, experience, and seniority, the Democrats were using metrics to make decisions. The Obama campaign trusted data over D.C. experience, and assigned 50 staffers to data analytics alone, compared with 30 staffers on the Romney campaign handling analytics. Overall, Obama’s campaigns had more expertise in tech, digital data, and analytics than had ever been seen before. Furthermore, the Democratic campaigns (especially Obama’s) attracted more talent from the tech industry.

“The tools changed between 2004 and 2008,” Trippi said. “Barack Obama won every single caucus state that mattered, and he did it because of those tools, because he was able to move thousands of people to organize.” (Miller, 2008). The availability of these tools, and thus the ability to mobilize these thousands of voters, were the fruits of the Democrats’ investments in digital media, big data and advanced analytics.

To get back on top, the Republicans invest in social, digital tools

The Growth and Opportunity Project produced by the Republican National Committee set a goal of “modernizing data and digital capabilities to provide tools for state parties and campaigns for voter contact,” and it seems that the Republicans have been putting their money where their mouths are. “The RNC began investing tens of millions of dollars in their data, digital and internet operations, opening an office in Silicon Valley ad hiring numerous tech-savvy staffers” reported the Atlantic’s Molly Ball.

After testing out various social analytics platforms, the Republicans began using a customized version of the software ‘Sprinklr.’ Sprinklr uses social media listening to feed real-time reports to campaign consultants, directors and communications staff in order to help them guide their messaging strategies. For instance, then Senate candidate David Perdue from Georgia began talking a lot about Ebola through interviews and his social media channels because Sprinklr told him that was a good idea.

On Oct. 23, not far from election day, he tweeted “The American people are concerned about Ebola, but Obama is just concerned about his political allies.”

He tweeted this message, says Wesley Donehue, CEO of GOP digital agency Push Digital, because Republican strategists “saw that the Ebola conversation really picked up in Georgia” – perhaps because Atlanta’s Emory Hospital was one of the major treatment sites – and wanted to capitalize on this opportunity to talk about something that was clearly important to voters. “When you’re running for office and your voters are concerned about an issue, you join the conversation too,” said Donehue (Kaye, 2014).

The RNC created what its Chief Digital Officer Chuck Defoe calls a “people-centered database,” which combined national voter data with social-listening data, as well as information regarding previous interactions with each other. Interactions, in this case, could be donating to campaigns or singing their petitions. “We are working with about a half-a-dozen Senate campaigns to deliver daily and weekly updates along with social analytics,” said the RNC’s Social Director, Lori Brownlee.

Brownlee also reported that, rather than just using Twitter and Facebook as “broadcast tools,” the Republicans “centered their plan around using social media as a strategic listening and data collection tool” (Kaye, 2014). This effort, the RNC said, would serve as the basis for a much broader rollout of such tools in 2016, accompanied by a bigger budget for data and additional staff.

This strategy is in-line with the theory proposed by Ceron, Curini and Iacus: social sentiment analysis works as a powerful complement to traditional polling. A complement – not a replacement – notes the RNC’s Chuck Defoe. The data reflect “what people are discussing right now, not necessarily people’s opinions,” he said. “Neither replaces traditional polling, which provides snapshot of the electorate in a controlled environment” (Kaye, 2014). The RNC thus invested heavily in these new methods of securing data and planning media, and in doing so, learned how to use data to truly “read their minds” and tell voters exactly what they want to hear.